New State Management for Red Snapper Is Driving Overfishing

Managers must take action or private anglers will likely catch 48% more than is sustainable in 2020

By all accounts, recreational fishing by private anglers is booming around the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, as fishermen head out on their boats to see if they can fill their coolers with some prized red snapper. With so many activities prohibited or unsafe because of the COVID-19 pandemic, many Gulf residents have turned to fishing as a way to continue to connect with the outdoors and spend time safely with their families and friends. The vast majority of fishermen are conservationists and are doing everything they can individually to follow the rules—they fish when the season is open, they only keep as many fish as they’re allowed and and they try to carefully release fish that can’t be brought back to shore.

But there’s a big problem—unless federal fishery managers step up and do the right thing soon, those rules being followed by anglers will likely allow at least 2 million pounds of fish in excess of a sustainable limit (148% of their annual catch limit) to be caught this year. This failure to prevent overfishing puts the recovery of red snapper at risk and threatens the future fishing opportunities of not just private anglers, but also for-hire captains and commercial fishermen.

The story for how we got to this crossroads is complex, but the solutions are simple. Managers can act quickly to make sure sustainable limits are set correctly and enforced. The question now is whether they will.

How did we get here?

During 2018 and 2019, fishery managers tested “state management,” which allowed each of the five Gulf states—Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas—to determine when and how private anglers should fish for red snapper in both their state and associated federal waters (from the shoreline to 200 nautical miles offshore.) As part of this new management system, the federal agency in charge of managing red snapper (the National Marine Fisheries Service—NMFS, or NOAA Fisheries) divided the annual amount of red snapper that the private recreational sector was allowed to catch under legally required and science-based limits into five slices, one for each state. In turn, the states took on the responsibility for setting management measures that would keep their state’s catch under their annual catch limit (ACL, or sometimes called “state quota”). This includes the responsibility to accurately monitor the red snapper catch of their anglers throughout the year and ensure that the sector stays below its limit. If overages occur, states pledge to do “paybacks”—essentially catching less in the following year to undo the damage to the stock.

But from the very beginning of state management, there was a significant problem. Each state was using its unique monitoring surveys and reporting systems to track the catch from their anglers. Unfortunately, because of the different choices made in designing and implementing each survey, the data they produced weren’t directly comparable. For instance, a pound of fish reported by the Snapper Check survey system in Alabama wasn’t equivalent to a pound of fish reported by Florida’s Gulf Reef Fish Survey. What’s more, the catch levels from each state weren’t able to be compared directly to the ACLs that were assigned to each state, because those were derived from a different survey run by NMFS that measured the recreational catch of the stock Gulf-wide. As a result, six different surveys were being run simultaneously in the Gulf to track recreational landings—one for each state and one by NMFS—and none of them could talk to each other. Comparing landings from these different surveys to the ACL is akin to trying to pay for something that costs $300 American dollars with 100 pesos, 100 euros and 100 Canadian dollars—you would not be paying the right amount. Without the ability to convert catch data between each type of survey, significant errors were creeping into management—errors that would be revealed to be allowing catch greatly in excess of sustainable limits.

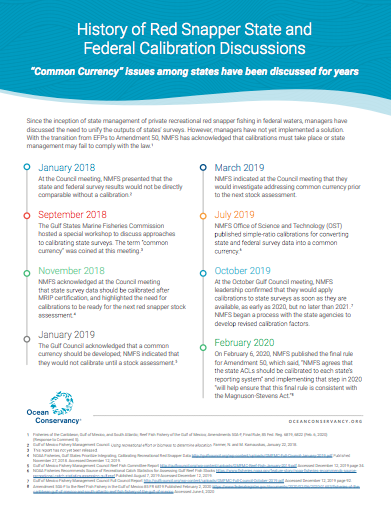

Managers from NMFS and the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council (the management body that develops plans for managing fisheries in federal waters) discussed the problem of needing to be able to convert these survey outputs into a “common currency” in public meetings throughout 2018 and 2019. In July 2019, scientists at NMFS looked into the problem and released “simple-ratio calibrations” that could be used as conversion factors for the surveys. With these conversion factors, each state would be able to calibrate its survey outputs to compare them to the state ACL. We applied calibrations and found that, in 2018 and 2019, anglers caught 2 million pounds each more than their sustainable limit. These overages didn’t trigger the “payback” mechanisms in the rules because the issues with comparing the surveys essentially hid them from view. These calibrations should have been the solution to the problem of overfishing, and the experiment of state management would have been a success if these ratios had been used.

But they weren’t.

Managers locked in a flawed management system

After less than two years of experimenting with state management, managers at NMFS and the Gulf Council moved to make the new system permanent. To do this, the Gulf Council passed Amendment 50 to the Reef Fish Fishery Management Plan, under the requirements of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA). That law sets out the guiding principles for how to manage fisheries sustainably to ensure we have healthy fish populations and fishing opportunities for the long-term. Two of the key provisions in the law are requirements to use the best scientific information available to make decisions and a prohibition from allowing catch to exceed sustainable science-based annual catch limits. Those ACLs are set at levels to prevent overfishing, as fishing in excess of those limits has serious impacts on the overall health of the stock. All fishery management plans and amendments have to comply with the MSA.

Strike one for sustainability.

NMFS was up next. In February 2020, the agency released its final regulations for implementing state management under Amendment 50. On the subject of calibrations, it’s worth reading NMFS’s text directly. NMFS agreed that state ACLs should be calibrated, and then they … did nothing about it. Instead, they admitted the regulations were insufficient on their own, contrary to their fundamental purpose of ensuring that fishery management is consistent with the law. Instead, the rule stated, “Implementing the calibrated ACLs in 2020 will also help ensure that this final rule is consistent with the Magnuson-Stevens Act.” But then NMFS made no move to actually carry out those calibrations. Ocean Conservancy wrote NMFS a letter in May asking for them to take immediate action to ensure fishing was sustainable for 2020. Their response: “This issue is best addressed through the Council process.”

Strike two for sustainability.

We’re running out of time to get this right

In June 2020, fishery managers will come together once again (virtually this time) at a Gulf Council meeting to decide whether they will do the right thing for red snapper. Across the Gulf, recreational fishing for red snapper has already started (most seasons start around Memorial Day), and initial reports suggest that anglers are catching a lot of fish. NMFS is bringing new calibration ratios to this meeting to present to the Council; we’ve already plugged these numbers in, and they show we should expect a minimum of a 2-million-pound overage in 2020 if managers fail to act. I say a minimum because that doesn’t account for ways in which this year may be different than previous years of fishing. For instance, using the conversion ratios to look at Alabama’s first weekend of red snapper fishing in May, we calculate Alabama anglers already caught 37% of their calibrated ACL. There have been three more weekends since then.

But the stakes are high. Private anglers have been catching significantly more than their sustainable limit for at least three years now. In 2017, the Secretary of Commerce illegally extended the private recreational red snapper season, resulting in an estimated 2.8 million pounds of extra catch above their limit of 3.8 million pounds. As we noted above, 2018 and 2019 each resulted in around 2 million extra pounds of catch because of the lack of a “common currency.” This has already caused harm to the health of the stock, and continuing to fail to take action will just dig the hole deeper. We modeled the impacts of these estimated overages and found that we could be erasing more than a decade of work to rebuild this stock to healthy levels (we are in year 15 of a 28-year rebuilding plan for red snapper). As early as 2022, we expect to start seeing real declines in the fish available if no action is taken, with the hardest-hit areas being the Gulf coast of Florida and Alabama, even if the productivity of the stock remains high. And the damage won’t be limited to the private recreational sector; every sector that fishes for red snapper stands to lose, even when the for-hire and commercial sector have fished sustainably within their limits for years.

What is clear—if managers leave the June Gulf Council meeting without a solid plan for how to immediately address the calibrations issues that are allowing for overfishing—that will be strike three.